DID THE JEWISH QUOTA DEPRIVE PEOPLE OF THEIR RIGHTS?

The leader of the institute of historical studies run by the government claims that the 1920 law limiting Jews from registering in university did not deprive anyone of their rights. Although politicians of the leading party distanced themselves from Sándor Szakály’s controversial statements, the latter was not dismissed from his post.

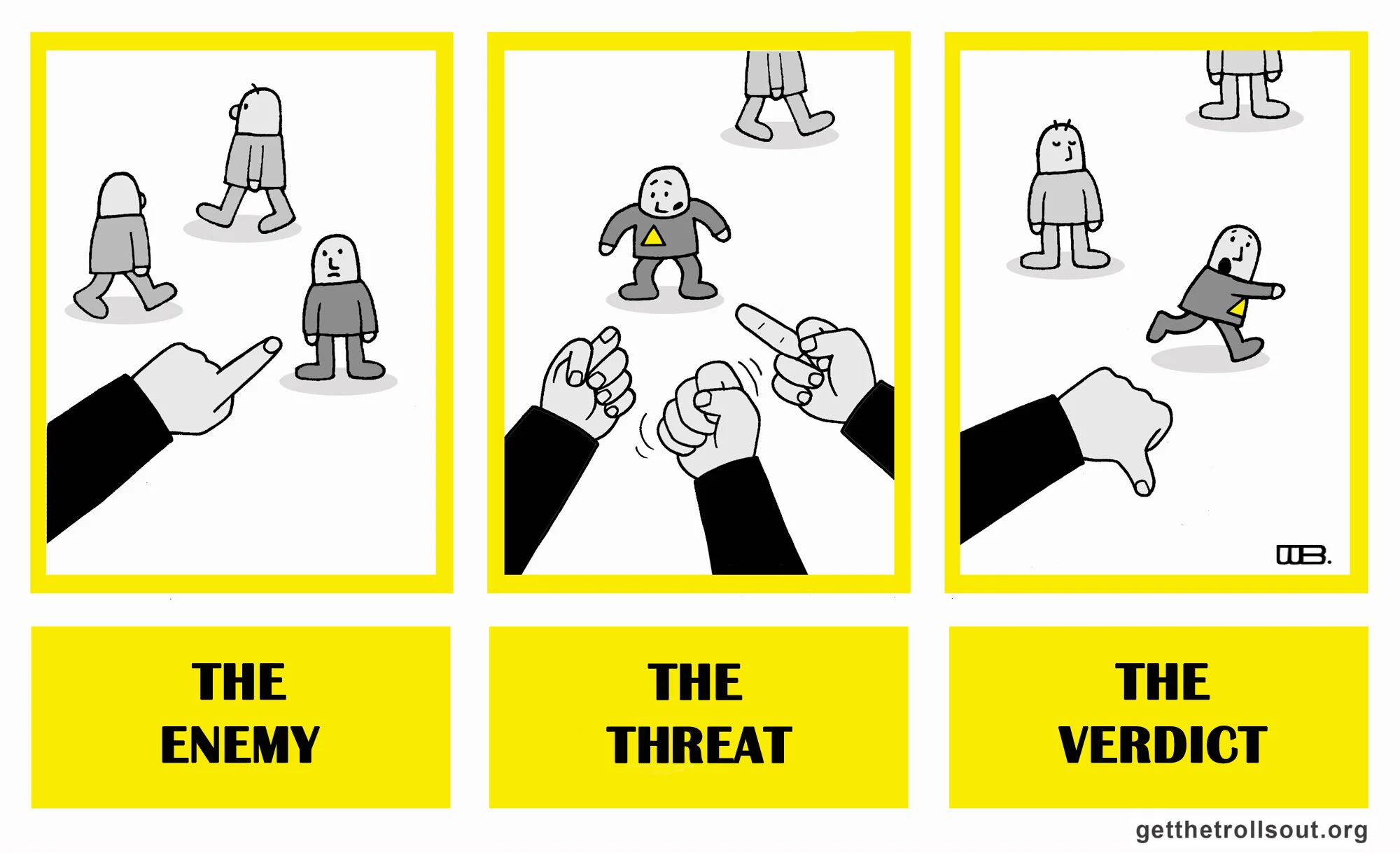

A cartoon by Bela Weisz for Get the Trolls Out!

By Dóra Ónody-Molnár

The statement

A few weeks ago, Sándor Szakály, director of the Veritas Research Institute run by the government, said in an interview with the Budapest Beacon that the numerus clausus had not deprived anyone of their rights. This law, considered by many to be the first anti-Jewish law, was enacted by the Hungarian parliament in 1920. The view generally held by historians is that its primary aim was to significantly reduce the proportion of Jews in Hungarian higher education and thus also in various fields of intellectual endeavour.

Szakály however claims that the measure was not directed against Jews, as the law does not even mention the word “Jewish”. According to his reading, the aim of the law was to ensure that the ratio of certain “ethnic species” and nationalities represented in Hungarian universities should correspond to the ratio of the population of each “ethnic species” or nationality within Hungary. In his opinion, the quota was only intended to help the middle class Hungarian refugees arriving from the Hungarian territories truncated by the WW1 peace treaty. While he admitted that the quota certainly did limit the rights of some, it “gave greater opportunities to others”.

The rebuttal

The above statement was however rebutted by several historians, including Ignác Romsics, who is currently considered in Hungary to be the most authoritative researcher on the period between 1919 and 1944. In a statement, the expert stated that “indeed, the word Jewish or Israelite did not appear in the text of the numerus clausus law; however, parliamentary records about instructions for implementation of the law and the practical application of the law clearly show that it was exclusively directed at the Israelite denomination or ‘nationality’.” Romsics said that, prior to 1918, there was complete freedom to study in Hungary, and the ratio of Israelite students in higher education was around 30%. By the end of the 1930s, this ratio had dropped to 3 or 4%, and by the early 1940s, it was down to 2 or 3%. He claims that this is closer to a complete deprivation of rights than to a mere limitation of rights.

Romsics added that there was a long-standing consensus with regards to this issue: “although other aspects arose in the press and parliamentary debates of that period, for a long time, no one disputed that the numerus clausus was a law specifically enacted against Hungary’s Jewish population. In recent years however, some have made statements which either dispute this or at least attempt to downplay the discriminatory effects of the law.”

Another well-known researcher on this period agreed with his position. According to Mária M. Kovács, proponents of the law at that time attempted – because of international attention – to hide the true purpose of the law, as they knew that discrimination on the basis of nationality or religion would have a negative impact how Hungary was perceived abroad. In her analysis, she writes that “it is for this reason that the law was enacted with a reversed logical order and with legal trickery: the solution was the idea of Bishop Ottokár Prohászka. This was to enact the Jewish Quota in a way that there would be no reference whatsoever to Jews in the main body of the text. The main text should only include a rule that is equally applicable to all nationalities and ethnic groups in the country, so that it can avoid any charges of discrimination. […] Only one difficulty had to be bridged in this respect: that the Jews (who mostly spoke Hungarian as their native language) were not considered a nationality, but a denomination under the Hungarian legal system. They solved this however by stating in the instructions for implementation that, from now on, ‘Israelites [are to be considered] as a separate nationality’.”

Mária M. Kovács completely rejects the claim that the law could have been in any way considered as positive discrimination, as young Christian applicants to university did not suffer from any disadvantage whatsoever before the numerus clausus was enacted. Even though, after 1920, only 6% of students could be Jewish, this did not lead to an increase in Christian applicants to universities. Thus, “in the twenties, the country’s universities in fact suffered from a chronic shortage of students.”

She believes that the statements of Sándor Szakály “explicitly aim to trivialize and thereby legitimize the anti-Semitism of the Horthy regime”.

The official historian

Since January 1, 2014, Sándor Szakály has been directing the newly founded Veritas Research Institute, managed by the Office of the Prime Minister and having a budget of 260 million HUF (about 700,000 GBP) at its disposal. The academic community of historians was decidedly unenthusiastic when the foundation of this new institute for historical studies was announced. Several voiced concerns that this institute would not focus on impartial academic research but would instead serve to validate and propagate the Orbán government’s official versions of history.

Few, however, were surprised by the nomination of Szakály. According to some reports, the institute was promised to him from the very beginning. The historian openly speaks of his connections to the right-wing, and his main area of research is the military under the Horthy era (1920-1944), and primarily its military elite. Over the last decade, he has focused more on disseminating information to the general public than on academic research. His work as a political journalist show that he is committed to changing negative opinions of the gendarmerie. In the early years of the 2000 decade, he also worked at state television channel Duna TV as vice-president in charge cultural programming.

Immigration procedures

Not long after his nomination, Szakály made statements that provoked a huge scandal (similar to the current one). He described the deportation of 15,000 Jews from Hungary to be killed at the Kamenets-Podolsk massacre in 1941 as “immigration measures”.

Because of this statement, Hungarian Jewish organisations and left-wing opposition parties demanded his dismissal. The government was not willing to do so, which (in addition to the issue of the controversial monuments) was the main factor in leading Hungary’s largest Jewish organisation to boycott Holocaust memorial events.

Business as usual

The follow-up to Szakály’s recent statements have proceeded according to the usual script: 1) a member of the leading political party or a person with close ties to the government makes an unacceptable statement connected with a sensitive topic in 20th century Hungarian history; 2) left-wing parties and the liberal intelligentsia protest vehemently, academic experts may also voice their disapproval; 3) a member of the government carefully distances himself/herself from the statements; 4) the person who made the controversial statements remains in office.

All this is the consequence of the government’s identity politics strategy, which manipulates historical memory in order to forge a common identity and to influence voting behaviour. Szakály’s statements now and two years ago can be understood as a defence of the much-disputed preamble to the Fundamental Law (Hungary’s new constitution), which was only accepted by the ruling party. The official view of history enshrined in the preamble infers that the occupation of Hungary in 1944 was a caesura which also carries the responsibility for the Holocaust.

The trivialisation of the numerus clausus law adopted in 1920 or the Kamenets-Podolsk deportation all contribute to the interpretation that, before 1944, i.e. while Hungary was a sovereign state, Jews were basically safe, and that the persecution of Jews only began under the German occupation; thus also the rehabilitation of the Horthy regime cannot be criticized either.

Szakály’s statements are in keeping with this. The most that can be said is that he overdoes it somewhat. The government cannot endorse the way that he pursues the logic which finds its expression in the preamble to the constitution, the monument on Freedom Square or the Hóman memorial. Politicians are better skilled than he at double-talk, or at what the prime minister calls “peacock dancing”.

It is not likely that Szakály is acting on instructions of the government when he makes statements that later require that members of the government distance themselves from them. However, a government which nominates individuals like Szakály does so knowing that they are bound to make this type of statements at any moment.